As a result of the research grant from the Arts Council of Wales, I am looking for expressions of interest from galleries, museums, schools, libraries, communities, festivals or anywhere else, in hosting the installation 'Isabella and the String of Beads'.

Here's the background:

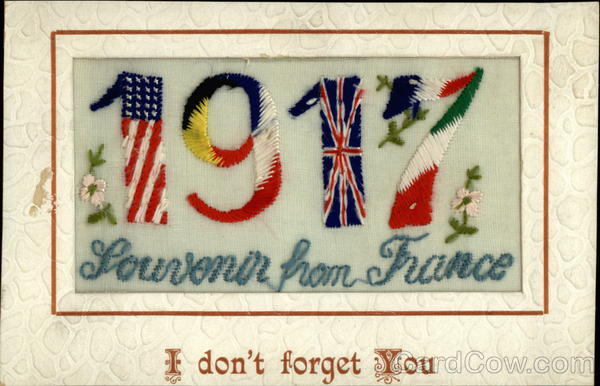

Unravelling the tale of what happened as she travelled has been like a detective story. She left no personal papers or diaries. Only her medical instruments and a string of beads tell of her war experience, but the words of others give clues as to how she might have thought and reacted, words both from writings of the time and from interviews with living women whose lives parallel Isabella’s in unexpected ways.

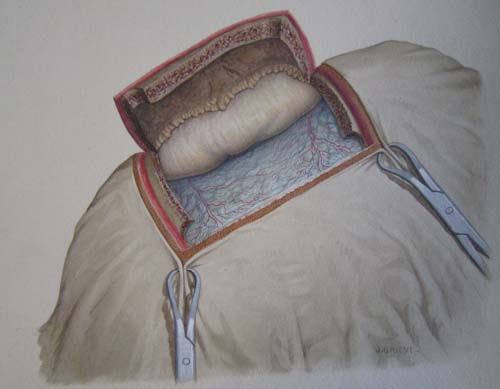

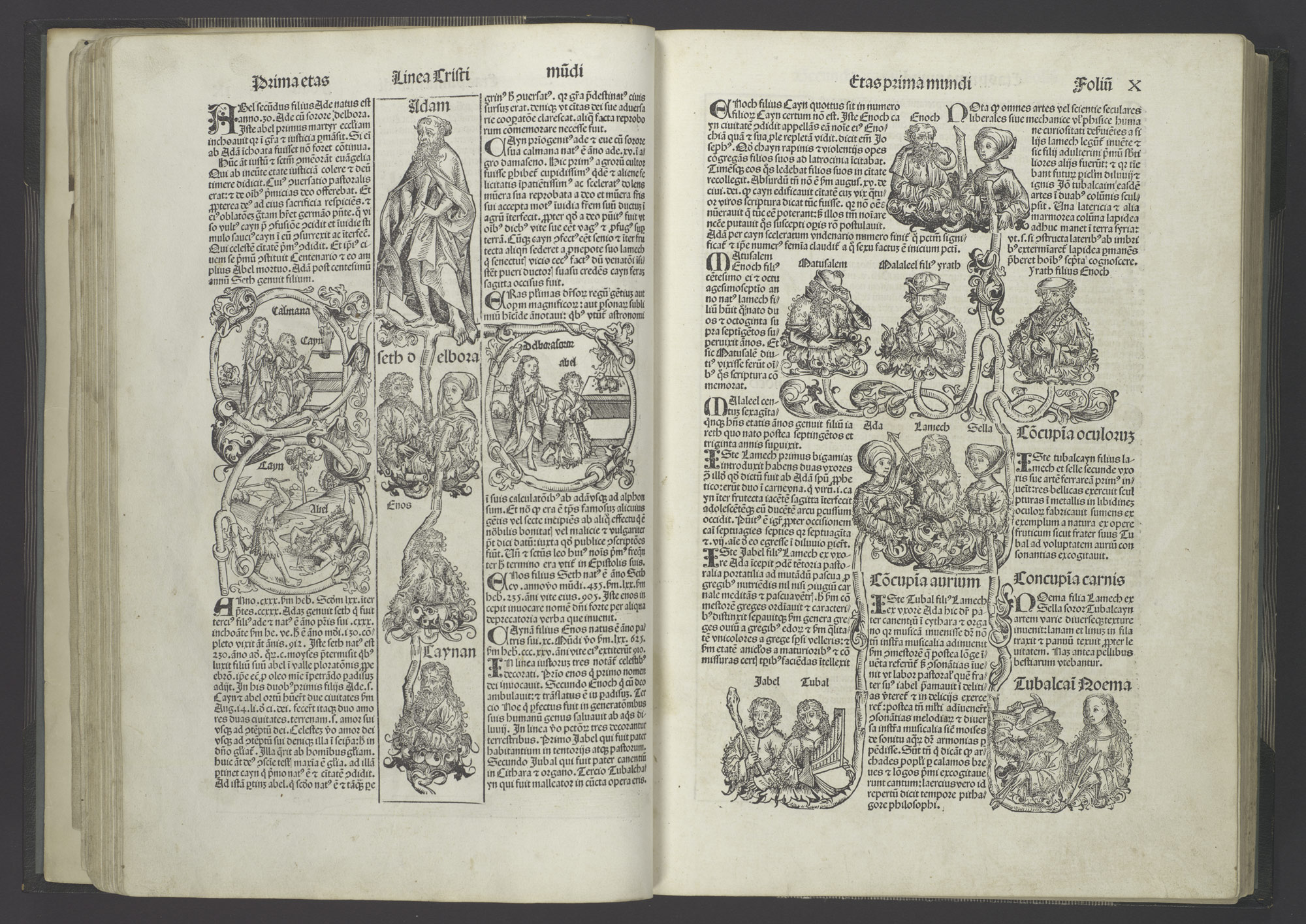

Alongside her original instruments, her story will be revealed through a life-sized replica of her uniform, a freshly-constructed sampler, a dissected 1910 anatomy text book, short films and lighting effects.

Here's the background:

In the 1890s there were four sisters, who, like many other girls of their day, were brought up to sew fine seams and prepare for marriage to a suitable man.

But the oldest, Isabella, grew restless and fought her way into studying medicine.

She had just qualified as a doctor when war came in 1914.

Leaving home, she travelled many miles and to mend wounded men instead of garments.

Unravelling the tale of what happened as she travelled has been like a detective story. She left no personal papers or diaries. Only her medical instruments and a string of beads tell of her war experience, but the words of others give clues as to how she might have thought and reacted, words both from writings of the time and from interviews with living women whose lives parallel Isabella’s in unexpected ways.

Isabella’s story will be told through a clue-filled installation that aims to give the viewer some of the delight of detection and discovery that the research has provided.

Alongside her original instruments, her story will be revealed through a life-sized replica of her uniform, a freshly-constructed sampler, a dissected 1910 anatomy text book, short films and lighting effects.

Isabella's story represents the story of many feisty women, so to make it accessible to a range of people, there will also be a portable version of the installation that can visit schools, libraries and community venues. Workshops will also be available to enhance engagement.

Please contact me via the contact form for further details and discussion.

Please contact me via the contact form for further details and discussion.