Courtesy of the Arts Council, I've been able to come up to London and see what I can find in the many archives, museums and galleries here. I've been looking for anything that will inspire presentation and help me to get into the spirit and aesthetic of the period.

Here are some highlights:

Here are some highlights:

The Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green had magic lanterns, a popular entertainment when Isabella was a girl. There was no TV and films were only in embryonic form by the time she was a teenager. There were no laptops or computer games, and for a girl, no Facebook, only posting letters and wiring telegrams. No plastic, so toys and games would have been made of wood, card, paper or metal.

In Tate Britain there was a 1900 portrait of a young Edwardian lady by Sir William Orpen.

It helps me, because it is hard to work out what colours clothes and rooms would have been from black and white photos.

The contrast with his war painting of 1918 shows something of the change people would have had to cope with.

From 1914, Edward Reginald Frampton painted the anguish of a young French couple as the young man went off to war:

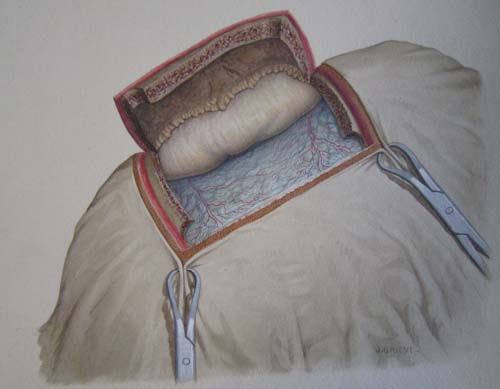

A visit to the Army Medical Services Museum in Keogh Barracks gave me a lot of information about the way the army has cared for the wounded over the centuries. I hadn't realised such care had a very long history.

The Hunterian Museum had some powerful images of war wounds, as well as Joseph Lister's dissecting kit, which was almost identical to Isabella's. The Foundling Museum told poignant stories of children whom their mothers had had to abandon.

In the Wellcome Collection there was a magnificently gruesome installation about the potential use of insects as food.

I was unexpectedly moved by the Souzou exhibtion of Japanese Outsider Art

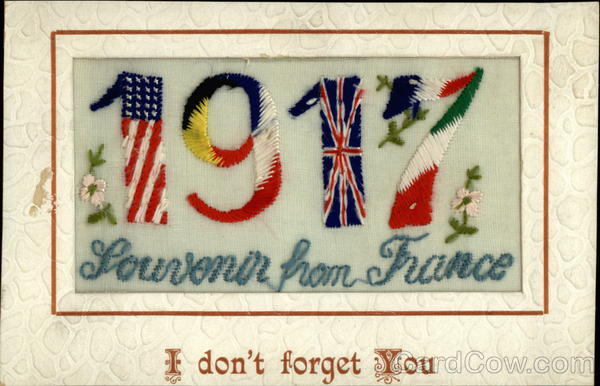

Satoshi Murita's embroidery on a blanket took my eye and reminded me of the sheer physicality of the sickness Isabella would have had to face. Blankets, sheets, bandages, smells, disinfectants, pus......

In their Medicine Now exhibition, a range of artists had created installations that explored different aspects of modern medicine.

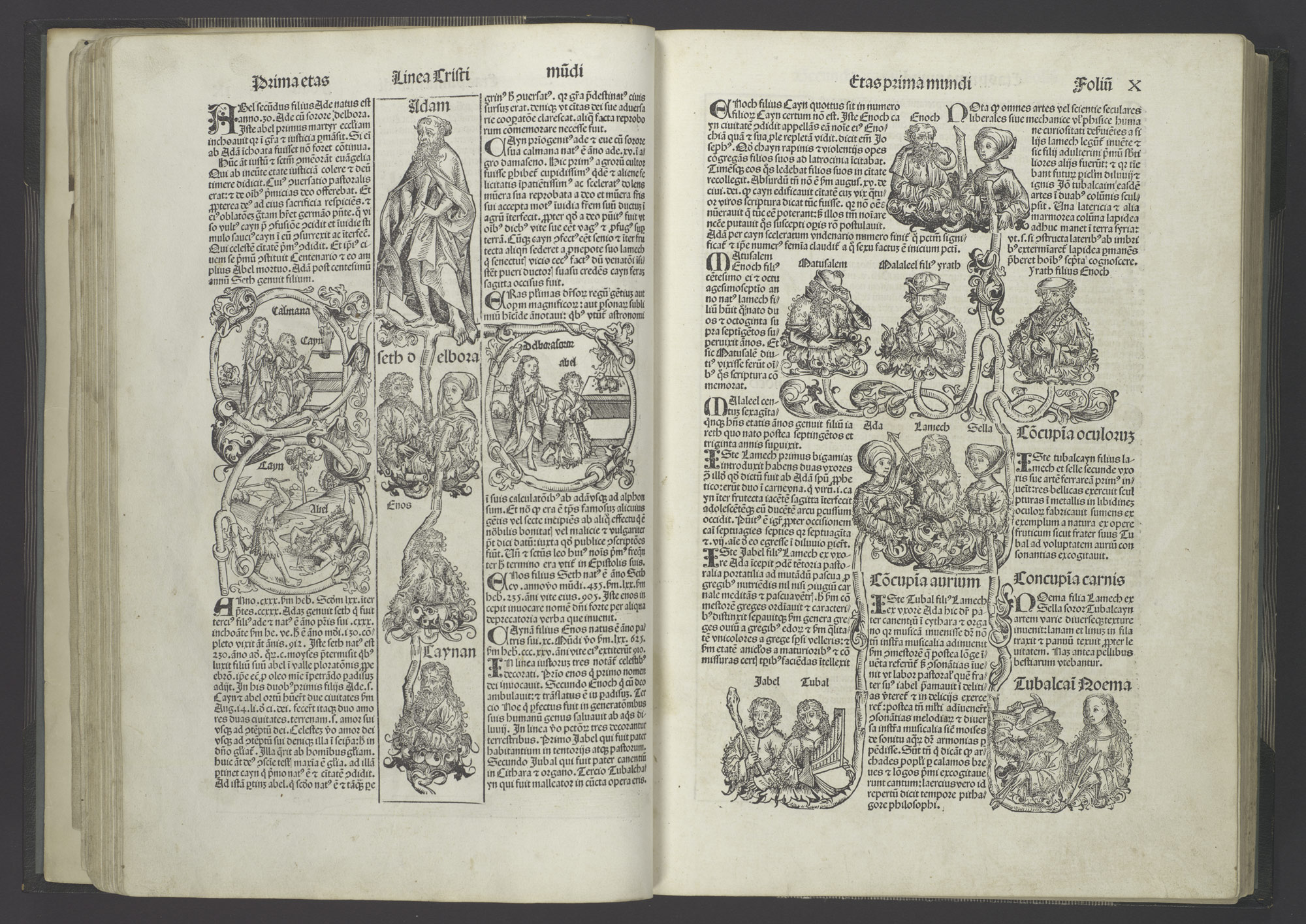

Cultural DNA

The difference between these artistically directed pieces and the historical and precisely accurate displays in the previous museums I'd visited was palpable. Each have their place, and that is one of the choices I will need to make in relating Isabella's story.

One artist had had a necklace created from the sequencing of his DNA. That linked in well with two of the concepts at the back of my mind in doing this project - legacy, and beads.

What consequences did Isabella's actions have for future generations? The knowledge that geneticists call a particular electron-microscopic view of DNA 'beads on a string' still haunts me. In the broader sense, what legacy did the deeds of feisty women of Isabella's generation leave for us, how did they change our conceptual DNA and inculcate the thinking of our culture? Was it all beneficial?